Once final casting decisions were made, we gathered sizing information from our principals and started gathering source photography that best depicted the late ’70s, early ’80s military clothing and weaponry in the film. What we discovered is that things have changed quite a bit in the thirty years and while most of the items were still available, there were still a couple of pieces that we still have no idea what they are.

Online resources proved too unreliable since the sizing specifications for military style clothes are bit odd — at least to us. And on top of that, most everything that turns up on a Google search are modern versions of the BDU (battle dress uniform) that feature lots of velcro and very different collars. The best option was to visit a military surplus store in person.

We traveled just north of the city to Army Navy Discount Center and were able to get just about everything we needed in one trip. The staff was knowledgeable and helpful and once they figured out we were sourcing costumes, they graciously offered up a production discount…even though it was just for the web and not the next Avengers.

The tactical vest worn by the USPF guards is one of the items that just confused us to no end. It’s soft like the liner to some motorcycle jacket and there’s a zipper down the front with odd silver snaps across each shoulder. It doesn’t appear to offer any protection like a bulky flak jacket might have, and it doesn’t appear to feature much in the way of gear support like modern vests do.

In the end, we purchased a modern tactical vest from the same store, Air Soft Atlanta, the same store that helped us with the firearms used in the video. We removed all of the straps and loops that could be taken off without ruining the structural integrity of the vest. And for the shoulder snaps, we bought a fastener kit from a Michael’s arts and crafts store and added them by hand. They are non-functioning and purely decorative but seem to fit the bill. Not perfect by a long shot, but we hoped the black-on-black nature of the outfit and lighting on the set would help to hide its shortcomings.

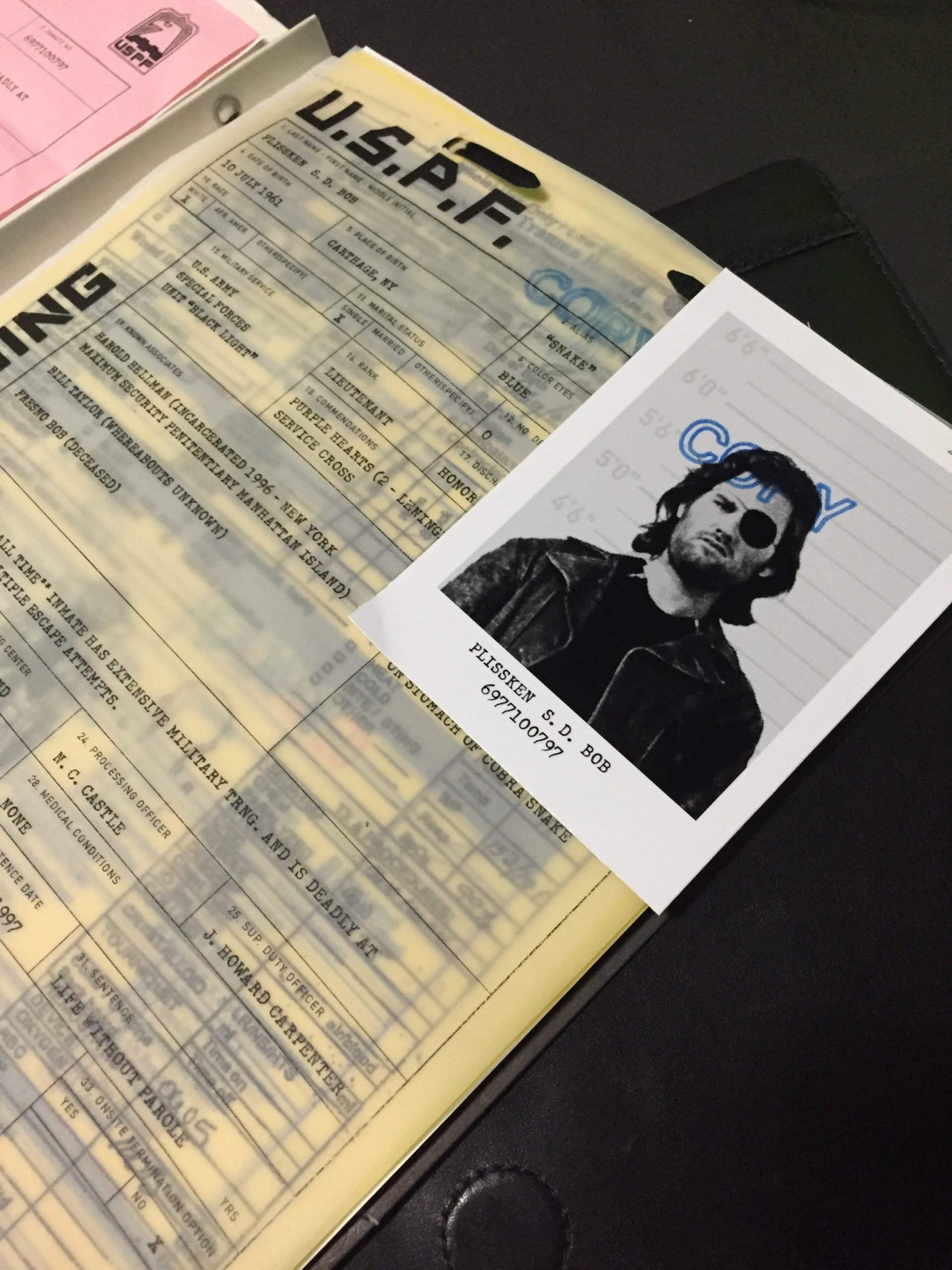

The USPF patches were easily sourced on eBay for about $15 from a dealer in Florida. Each order shipped with one of the classic EFNY version patches and one featuring the updated logo for Escape From LA. So just add seamstress to the many duties our director fulfilled on this project.

The helmet was another eBay find from some individual that had purchased a whole batch of them from some police force that probably upgraded to something nicer when they got their Patriot Act funding. Again, sizing was a concern with most research stating that these particular Premier Crown Corp Model C3 Riot Helmets came in a universal size and an XL. The seller wasn’t too sure what he had but for $50 it seemed like a reasonable gamble since the helmets new are five times that cost.

The unique feature of the USPF helmets in EFNY is the odd double face shield. It sort of makes sense in that these riot helmets have mounting points for a wire type cage to fit over the clear visor. We can only assume Carpenter thought the cages looked too Kent State 1970 and not enough Dystopia 1997 and opted for the giant tinted sheet of Lexan to help sell the futuristic vibe.

A trip to a local home improvement store netted some sheets of acrylic and a heat gun but the samples purchased ended up being too thick to bend and mount properly. A quick search on Amazon turned up some 0.02″ and 0.04″ sheets of PETG (Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol-Modified). Add in a $10 window tint kit and we were in business. Note the wonky nature of the tinted shield in the picture above — artifacts from the crude heat gun approach to bending the plastic no doubt. But for a minute or so of screen time, you’ll be amazed at how many mistakes like this you are willing to accept.

On a related note, applying window tint is way harder than it sounds. We went through several kits before we had something that wasn’t all bubbles and spots. And even then, by the end of the shoot it was looking a little worse for wear and peeling up at the edges. In hindsight we probably should’ve just stopped by a tint shop and had a professional do it.

Not having any experience with replica or airsoft guns, our reaction when we visited Air Soft Atlanta’s showroom was probably pretty similar to most folks that hold a metal, electrically powered airsoft rifle for the first time: “Holy shite! This thing looks and feels real.” If not for the silly bright orange flash suppressor on each barrel, there is almost no chance the average viewer will be able to tell the difference on screen.